Episode 67. Building the US-India Relationship During the Trump Administration

Admiral Davidson & Ambassador Juster discuss their joint efforts to strengthen the US-India security relationship despite India’s military dependence on Russia, tense relations with Pakistan & China, and its policy of strategic autonomy.

Episode Transcript:

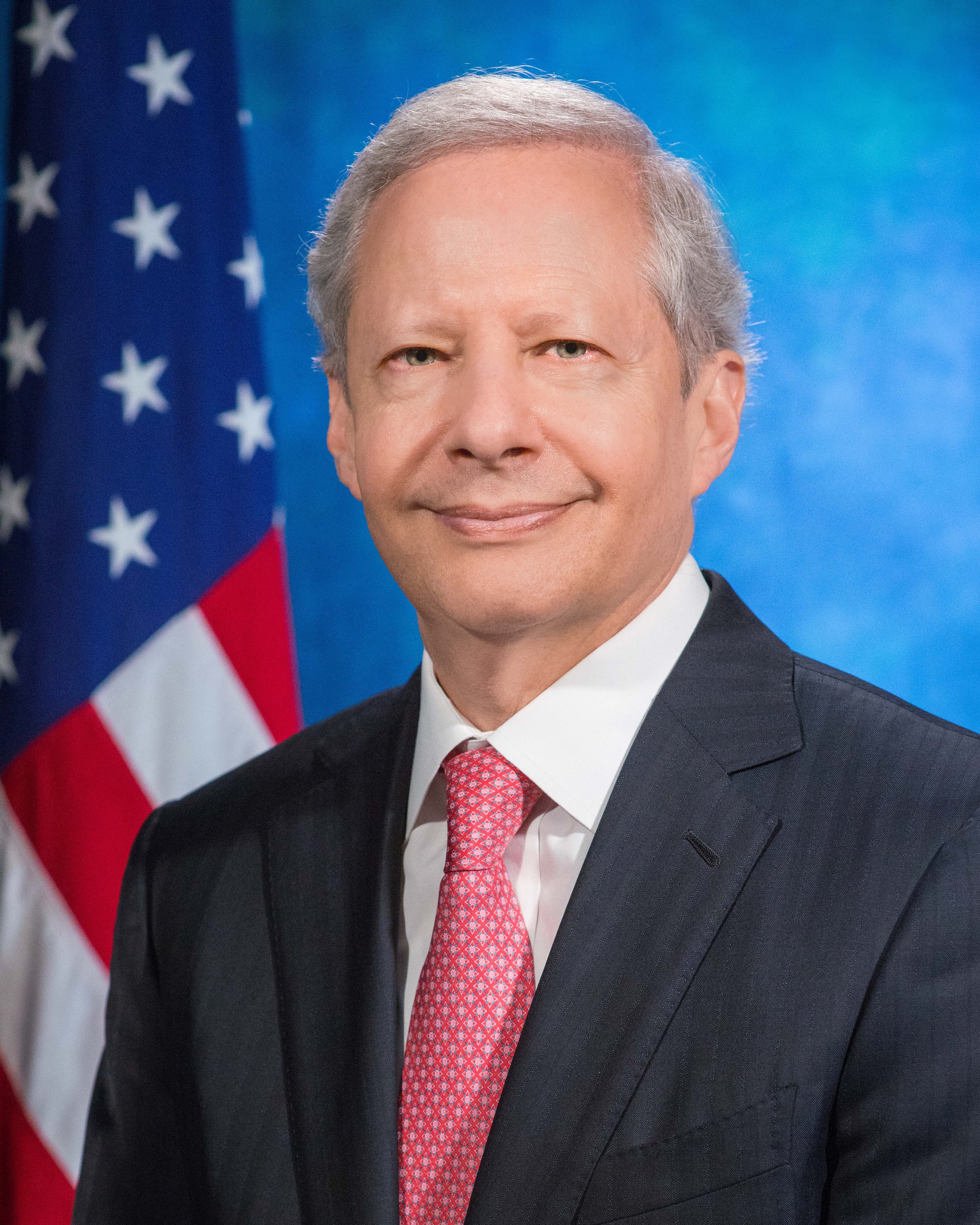

Amb. McCarthy: [00:00:16] Welcome to a conversation in the Academy of Diplomacy series, the General and the Ambassador. Today we're going to entitle this podcast, "The Admiral and the Ambassador," as we have two special guests, Admiral Phil Davidson and Ambassador Ken Juster. Our podcast brings together senior U.S. diplomats and senior U.S. military leaders in conversations about their joint work to advance U.S. national security interests in different parts of the globe. The General and The Ambassador is a production of the American Academy of Diplomacy with a generous support of the Una Chapman Cox Foundation. I'm Ambassador Deborah McCarthy, the producer and host. Today, we will focus on the U.S. security relationship with India. Our guests are Admiral Phil Davidson and Ambassador Ken Juster. Admiral Phil Davidson served as the 25th Commander of the United States Indo-Pacific Command from 2018 to 2021. Just prior, he was the commander of U.S. Fleet Forces, Command and Naval Forces, U.S. Northern Command. He previously served as the Commander US Sixth Fleet and the Commander Naval Striking and Support Forces NATO while simultaneously serving as the Deputy Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Europe and U.S. Naval Forces Africa. Ambassador Ken Juster served as the U.S. Ambassador to India from 2017 to 2021. He has served in many other senior government positions as well as in the private sector. He was the deputy assistant to the President for International Economic Affairs on both the National Security Council and the National Economic Council. Under Secretary of Commerce, Acting Counselor of the State Department and Deputy and Senior Advisor to Deputy Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:02:10] Admiral Davidson, Ambassador Juster, welcome to The General and The Ambassador Podcast. Thank you for taking the time to join us. I wanted to start by asking a bit about the framework of our security relationship. In 2015, the U.S. and India renewed their Defense Framework Agreement for another ten years. In 2016, President Obama designated India as a Strategic Defense Partner. President Trump deepened the security relationship, granting India what is called "Strategic Trade Authorization Tier One Status." Also, under the Trump administration, a new 2 + 2 dialogue was launched with defense and foreign ministers. Three additional bilateral defense agreements were also signed and joint military exercises were expanded. Many of these questions were taken as part of the shift in U.S. foreign policy towards Asia. President Obama led an effort to rebalance U.S. interests to Asia and the Pacific. President Trump subsequently launched the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy. So my first question for both of you how did President Trump's Indo-Pacific strategy differ from the Obama rebalance, and what were your missions in that regard?

Amb. Juster: [00:03:34] The US-India relationship has continually expanded and deepened over the years, and it's really been transformed over the last 20 plus years. And part of that is covered in your question. The pivot to Asia and the rebalancing was a US policy indicating its importance that it was giving to that region. The Indo-Pacific strategy is really a regional policy in which President Trump, along with Prime Minister Abe of Japan and others, started speaking about the Indo-Pacific as a region connecting India and the Indian Ocean to North and East Asia and the Pacific Ocean. I say India to all of South Asia and having a geography that ultimately was expanding from the east coast of Africa to the West Coast of the United States, and now every country in the region has bought into the concept of the Indo-Pacific, except China and Russia, and they've enunciated individually and collectively a set of principles for a free and open Indo-Pacific based on the rule of law, the peaceful resolution of disputes, freedom of navigation and overflight and trade, and the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the countries in the region. So we're now in the process of building out the architecture for the Indo-Pacific. But this has been a continual evolution and building upon an earlier rebalancing and pivot to a broader strategic view of the overall relationship working in conjunction with other countries. And I'm sure we'll get to the subject of the quadrilateral grouping of the United States, India, Japan and Australia, but that's a further effort to build out the architecture of a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Adm. Davidson: [00:05:25] I see it exactly as Ambassador Juster does. It's deepening and broadening of the relationship. For me personally, these things began with subordinate defense approaches. One of the things we were working on very early was to come to a communications agreement that would be reflective of the deepening relationship in the transition to a free and open Indo-Pacific and the Indo-Pacific strategy. So my consultation with Ambassador Juster was frequent and between our teams was routine, I should say, to really make sure that we were getting the things accomplished in a way that supported that broadening relationship but didn't get out too quickly in front of the overall policy approach. So Ken and I spoke early in my tour as the US Indo-Pacific Command commander, and as I mentioned, we had to consult quite frequently. I was very pleased with the relationship and pleased to be alongside can just.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:06:25] Well as part of this deepening relationship, I mentioned the launch of the 2 + 2 dialogue and as it involved our Secretaries of Defense and Secretaries of State. How did you and your teams work to ensure that these meetings were were successful?

Amb. Juster: [00:06:42] Again, let me just build on what Admiral Davidson has just stated and reiterate on my part. Again, my tremendous respect for Phil and admiration of the working relationship that we develop not only at our level, but with our teams. And part of that was responding to crises that occurred, whether it involved cross-border terrorism from Pakistan or issues relating to China on the northern border. But part of it also related to coordinating on trying to get initiatives done in conjunction with these two plus two dialogues. The 2+2 was a dialogue among defense and foreign ministers for the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Defense on the US side. And it really was a breaking out of this grouping from what had been a very broad set of dialogues in the previous administration. By breaking it out, it was easier to schedule meetings, it was easier to focus on some critical issues, and it was easier to get deliverables done in advance of meetings. And so one of the biggest accomplishments that Phil just mentioned were these foundational agreements between our defense establishments and these have been on the table for 10, 15 years and we were actually able we had just recently before we began, the countries had concluded a logistics agreement. But as Phil said, it was a secure communication agreement referred to as COMCASA. And then after that, a agreement on sharing geospatial information referred to as BECA, and also an agreement for information sharing among our industries of classified information. And it was the 2+2 dialogues that actually served as action, forcing events for getting these agreements done as we spurred each of our negotiating teams forward and coordinated on that. And ultimately, the 2+2 also played a critical role in resurrecting this Quad dialogue that I had mentioned among the four countries the United States, India, Japan and Australia. And the 2+2 even met during COVID in person in India in October of 2020. So it indicates how important that dialogue was.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:08:57] Well, Ken, can you explain what the Strategic Trade Authorization, Tier One, meant in this context for India?

Amb. Juster: [00:09:05] Well, this was a additional designation to India so that it could get enhanced access to what are known as dual use items. Those are items that have both a civilian and military application. When I first began working on U.S.-Indian relations in 2001 as Under Secretary of Commerce, many Indian companies were on what is known as our entity list, which forbids the export of dual use items to India at all. And part of what we did in transforming the relationship was figured out a glide path for getting companies off of the entity list, for expanding India's eligibility for dual use items, and for also making sure that India developed internally the export control regimes to ensure that such sensitive technology ended up where it's supposed to be and was not diverted elsewhere. And this ultimately laid the foundation for the civil nuclear deal. But what was important is that we have gradually given India increased access to US technology without the need for specific licenses to the point that they're treated now really in many ways like a NATO ally, even though they are not an ally, they're a partner of ours.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:10:22] During your time, there were many other high level face-to-face meetings. President Trump hosted Prime Minister Modi in the United States in 2017 and the President visited India in 2020. How important was the President's personal engagement with Prime Minister Modi, and what were the results?

Amb. Juster: [00:10:43] I think it was extraordinarily important and I would add in there as well. When the prime minister came to the United States in September of 2019 for what was known as a "Howdy Modi" event in Houston with over 50,000 people, which then led to the President's coming to India in February 2020 for an event with over 100,000 people at a stadium in Ahmedabad in India. But what you have here was a very strong relationship between President Trump and Prime Minister Modi that set the overall tone for the bilateral relationship and provided a lot of the impetus for getting individual initiatives done. If that was not a good relationship at the top, it would have infected some of the activities we were trying to accomplish below that, whereas a very positive relationship at the top helped accelerate those activities and use their meetings as ways to accomplish even more together.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:11:43] Well, meetings of our presidents, prime ministers and high level officials entail a lot of work on the part of teams. Can you give us a flavor of the work that your teams had to do to make these encounters successful?

Amb. Juster: [00:11:59] Well, as you say, and I also defer to Phil in terms of the military side. There's a lot of different elements going on all the time on the relationship. But a high level visit focuses the attention on trying to get certain things done. So when the leaders get together are the senior officials, they can make announcements that move the relationship forward. And because we had a number of military visits from all all the services, we had joint exercises, we had diplomatic meetings, all of that spurred us to both work together effectively, internally, but then also work with the Indians constructively to try to accomplish initiatives. And as Phil said, it was very gratifying to host members of his team as they came to India and to be with him. And he hosted a visit, a very significant visit from India's Minister of Defense, Minister Sitharaman.

Adm. Davidson: [00:12:59] Personal relationships are important even in the military business. Much of my peer group and even a few years junior to me in India had very, very close relationships, had been trained in Soviet and then Russian systems, certainly for those of my age. So trying to establish those relationships and build confidence in what we are talking about and what the what the agreements were meant to achieve and their advantages both to India and to the United States depends on those personal relationships. So it takes time and effort even from Hawaii. India is a really long way away and investing the time and energy it takes to to host in Hawaii to host on the mainland, as we say, and then again in India is very, very important.

Amb. Juster: [00:13:48] If I could just add one point to that. One of the interesting aspects of COVID has been the ability of groups to relate to each other over the Internet, through Zoom and other types of video conferences. But what has been missing has been the face-to-face contact, which does play such an important role. And I think the best example of that was when Phil and his team hosted, as I mentioned earlier, a Minister Sitharaman and a delegation from the Indian defense establishment, both the National Security Council and the Defense Ministry in Hawaii at the headquarters of INDOPACOM. It was a extraordinary experience. You could see as the Indians came in and and let me tell you, the INDOPACOM group, led by Phil, did an unbelievable job in terms of every element that was planned and what they showed the minister the hospitality, but bringing them into the inner workings of INDOPACOM and its capabilities really made the Indians appreciate the significance of the US-India defense relationship and I think played a key role in getting these enabling agreements or foundational agreements signed and increasing the level of our exercises and even increasing the sale of US weaponry to India because they saw the added competence and capabilities they would get from a deep relationship with us. And that would not, in my opinion, have happened as easily and smoothly without the personal relationships and the face-to-face meetings that we had.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:15:29] Well, despite the growing ties with the U.S., India doesn't have alliances, as you mentioned, and practices strategic autonomy in its foreign affairs. At the U.N., for example, during the Trump administration, India voted for a U.N. resolution calling for the U.S. to drop its recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. And more recently, it abstained twice on recent U.S. led resolutions condemning Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Can you explain how India balances its closer relationship with the United States with this policy of strategic autonomy?

Amb. Juster: [00:16:09] Well, one of the things you appreciate when you live in another country as an ambassador is looking at issues from their perspective. And India sits in a different historical and geographical position than the United States. It sees itself first and foremost as a civilizational power that's been around for over 5000 years. Secondly, it is in a region where it's got China on its border. It's near to Russia, and it has always wanted to avoid being subordinated to another country. This comes out of its colonial past in part. And so during the Cold War, it was a key country in the Non-Aligned Movement. And since the end of the Cold War, as you said, Deborah, it has sought to maintain strategic autonomy, which means that it doesn't have any alliances. It has strategic partnerships, including with the United States, but it also believes in having good relations with every country, both to be able to balance them off against each other, to the benefit of India, to promote what it hopes is a multipolar world in which it is one of those poles and to maintain its own active leadership on the world scene. The challenge for India is that the world as it's developing, doesn't always cooperate with that view of multipolarity, and they have to balance. They've had a long historical relationship with Russia. Again, it goes back to the Cold War when the United States really leaned more toward Pakistan and India ultimately did toward the Soviet Union and got most of its weaponry and military equipment from Moscow.

Amb. Juster: [00:17:50] And even as it started to diversify that over the years, it still has 60 to 70% of its military equipment from the Russians, and it needs spare parts and other material and also gets new equipment that the United States might not provide to it because it's too sensitive, such as nuclear powered submarines. And India does not want to see Russia and China teaming up against it in its northern border and in the region. So it has sought to maintain a relationship with Russia to balance out that equation in the region. But as it gets closer to the United States, it raises sensitive issues about how sophisticated the technology can be that we give to India. If that technology is sitting next to Russian technology that can pick up the software and things of that nature. And now you see India in a bit of a dilemma because Russia is committing atrocities in Ukraine. India wants to not alienate Russia in case it needs Russian spare parts should the Chinese attack India in the north. But it also realizes that its own principles of territorial integrity and sovereignty and peaceful resolution of the disputes are being violated. And we'll have to see how that situation evolves over the next several weeks. And it may be that the atrocities that are being committed by the Russians simply become too much for India or any other country to put up with.

Adm. Davidson: [00:19:21] You know, one of the things that transpired very early in my tour days into it was Prime Minister Modi's speech at Shangri-La, which in general converged around the idea that Prime Minister Abe and President Trump had put forth with our respective visions on a Free and Open Indo-Pacific. I thought that was an important statement to the whole of the region. Many perhaps don't know that the Shangri-La Dialogue is an event of incredible geopolitical and diplomatic importance in Asia. And when Prime Minister Modi outlined again what I call convergence around the Free and Open Indo-Pacific and made it clear that partnerships were possible. Certainly our experience and our partnership with the embassy there and New Delhi was to deepen that partnership through the foundational agreements that that can highlight. In addition to working on the on the personal sides, you do have to work those issues that become irritants in the relationship, the US military's relationship with Pakistan. The fact that there were Pakistani liaison officers in the US Naval Forces Central Command headquarters in Bahrain. These were issues that had to be discussed and was one of the things that really drove me to an approach that involved transparency with the Indians to make sure they understood what kind of information would or could be shared with the Pakistanis over an NAVCENT, as we call it, for short. But then as things moved forward in the relationship, what might we do on a US to India basis? That was all kind of brought to a head during the tensions along the line of actual control, which started in February of of 2020 and the relationship that we were able to build based on some of the actions that we took there.

Amb. Juster: [00:21:18] Phil has pointed out a very important issue from the Indian perspective, which is their sensitivity about our relationship with Pakistan, just as we're sensitive about their relationship with Russia. And it shows that it's a complicated process that needs to be managed. But I would submit that the trends continue to move into our in terms of a favorable US-India strategic partnership.

Adm. Davidson: [00:21:43] Full agreement for me.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:21:45] Well I did want to ask a question on the relationship with Pakistan and how we manage that. When there was that military clash that you mentioned along the border in 2019 as Pakistan falls under the area of responsibility of Central Command. I wanted to ask you, Admiral, how you worked across the commands when these tensions increased and when they had the clash in 2019.

Adm. Davidson: [00:22:12] Yeah, I'm sorry. I did get the date wrong was February 2019. I was thinking about it all too well because I was actually in Washington when it occurred. There's a responsibility between the combatant commanders to keep each other informed about those issues that move along the seams or the borders between combatant commands. I actually don't have much issue with where the the border is actually drawn between Central Command and Indo-Pacific Command when it comes to Pakistan and India, because the issues there are generally rooted in policy issues of the United States, and that's not where combatant commanders should be trotting around. That then leaves it to the appropriate level of bureau there at the State Department and at the Department of Defense to work through those issues. But in February of 2018, when we greatly increased the information that we were sharing with Indian authorities, Indian military authorities, I should say, and my own dialogue was stepped up with Admiral Lanba, the Chief of the General Staff, in India at that time, providing that information, helping to clarify again, what was the information that would be shared with Pakistan? How does it affect Pakistan's understanding of what's going on between India and China? How might that information move from Pakistan to China, which it would not, because there wasn't any common information here. But one of the first things that India did is they moved naval forces to see that having that understanding about both to the west of India and to the east and the Bay of Bengal, how those forces would be considered by INDOPACOM in the Bay of Bengal and to the west of India and the North Arabian Sea, for example, or in the western Indian Ocean by CENTCOM, was very, very important to the leadership there.

Amb. Juster: [00:24:02] If I can just add a quick anecdote that I recall from this period of time, and I believe it related to February 2019 when there was a cross-border terrorism incident emanating from Pakistan. It may have been several weeks later when there was an Indian retaliation for it and there was a dust up in the military. But at one of those points, most of the senior US officials were over in Singapore or Vietnam preparing for meetings with the North Koreans. And I remember vividly getting a call from Phil and we really were coordinating in terms of what we needed to do in the region and with the Indian government and more broadly to try to keep calm during this incident and make sure that it didn't escalate into something that would be more troubling. And so that to me was a very memorable incident where the two of us who were actively involved in what was occurring spoke to each other, coordinated before we could even get direction fully from folks in Washington because they were preoccupied with North Korean diplomacy at that time.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:25:10] In 2016, India announced a decision to buy more equipment from Russia, specifically S-400 missiles. Though this transaction hasn't been completed, it could lead to sanctions by the United States under a law called the U.S. Countering America's Adversaries through Sanctions Act or CAATSA. Can you describe how you tried to discourage this transaction and other purchases while, you know, seeking to deepen our security relationship?

Amb. Juster: [00:25:43] This is, say, a troubling element of the relationship, in my opinion, CAATSA Legislation was enacted really after the S-400 deal had been completed. The Indian government had come to the United States during the Obama administration, had sought to discuss missile defense purchases and they were turned off. The US government would not do it, in part because I think there was a concern of an imbalance that might develop between Pakistan and India because these missile defenses are used both for incoming aircraft really from China as well as from Pakistan, and also because it had very sensitive technology. So the Indians pursued the deal with the Russians for the S-400 system, which has certain capabilities that the United States simply doesn't have, in part because we don't have neighbors that we have to worry about having planes coming in over the border that might attack us. Our systems that may be somewhat comparable are also vastly more expensive. So the Indians had gone ahead and basically concluded the deal when the CAATSA sanctions were enacted by the Congress. Not really focused on India, but focused more broadly on concerns about Russia and other terrorist countries that might provide weaponry. So I didn't feel personally that we had a real strong case to dissuade the Indians from the S-400 deal. I think there's a broader issue of India's ability to get sensitive US technology if it also is buying sophisticated Russian technology.

Amb. Juster: [00:27:23] And yes, our position was to try to say to the Indians that it would be better if you didn't buy this S-400 equipment. But I never felt we had a strong case to say that you really shouldn't buy it. And in fact, I think if we impose CAATSA sanctions and again, part of this has now been changed by Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the whole panoply of sanctions that will be imposed and are imposed on Russia. But if we impose sanctions on India, a country that for 20 years we've been trying to increase the level of trust and reliability that will damage the relationship. Because the last time we did that was in 1998, when India did a nuclear test. It wasn't a nuclear weapon, but a nuclear test. And it happened years earlier when they did a nuclear test. And these sanctions have left a very sour taste with the Indians, and we've had to overcome that in developing the strategic partnership. So to invoke the cats of sanctions on really what has been a done deal, I think would be a serious step backward. We have to have a broader strategic discussion with India on how far it can go purchasing both Russian and American equipment. But I would divorce it from the S-400 and that cat's issue in my opinion.

Adm. Davidson: [00:28:36] From my chair, Deborah, the issue of CAATSA waiver and whether it was even possible with the S-400 purchase was the issue at hand. Much of my coordination and collaboration had to be done back in the Pentagon bureaucracy and with Capitol Hill to get everyone to understand what the level of involvement was really. The nearly 60% is the number I use in in my head of Russian equipments where the the Indians are required to purchase the maintenance, the ammunition, so things like that to replace that. And that is routed back in Cold War purchases and beforehand. So the issue of what a CAATSA waiver be possible or acceptable to the United States in this case and some of the technical ramifications of that and how it might affect US systems that were actually lined up to be sold to India were the issue at hand.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:29:33] I also wanted to talk about the India-Iran relationship, though India joined in early votes in the International Atomic Energy Agency's condemnation of Iran's nuclear program and stopped importing Iranian oil, it has continued friendly relations with that country. How did the India-Iran relationship affect your efforts to strengthen our own bilateral security relationship?

Amb. Juster: [00:30:02] Well, again, I go back to the notion of strategic autonomy and India's desire to have good relations with all countries. And they've had a long historical relationship with Iran and like to keep that relationship on a positive track. That said, India in recent years itself has diversified its relationships in the Persian Gulf, in the Middle East, and now has much stronger relations with the United Arab Emirates, with Saudi Arabia, and even with Israel. And so Iran has become less significant in India's own broader policy and part. It has many Indians working in the Gulf states that it needs to be concerned about also. But India has great energy needs, and one of the countries that supplied oil to India was Iran. And it was difficult for India to agree to eliminate imports of oil as the United States was trying to put pressure on Iran. Nonetheless, they made the strategic calculation that if this was something that was of great importance to the United States, they would make the sacrifice in a sense of stopping imports from Iran, potentially irritating the Iranians, and hopefully getting that oil from other sources. But they would ideally like to see a relationship with Iran and the West that is sufficiently positive that India can continue its own relationship with Iran, and that's part of their broader vision and view of international affairs. But the Iranian issue, while difficult, did not present a impediment that was overwhelming in terms of the US-India strategic partnership.

Adm. Davidson: [00:31:49] So interactions that I had with Indian military officials seldom focused on issues in around Iran and India's relationship.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:32:00] Well, the last country I'd like to explore before we get to my my wrap up question is India's relationship with China? They share a 2100 mile disputed border. And during your time in 2020, there was a series of skirmishes and a violent clash between Indian and Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley in the region of Ladakh. So let me start with you, Ken. How would you describe the India-China relationship?

Amb. Juster: [00:32:30] You know, at first I would say at the outset, we've talked about Russia, we've talked about Iran. We didn't talk about North Korea, but we could and we've talked about China. So you see what an interesting geographical position India is in and the range of challenges you have. And in building the relationship. It's what makes it fun to have been ambassador and I'm sure for Phil, fun to have been the head of INDOPACOM. But the India-China relationship has been very uneasy over the years. They had a war in 1962, in part because of issues relating to Tibet, the Dalai Lama had fled to India, and in part because there was an delineated border between the two countries, which is still the case. They talk about it as the line of actual control, but there's no firm boundary. Nonetheless, they have tried to work out certain modus operandi over the years to manage the relationship, and they worked out a series of protocols on border issues and where each side could patrol without getting into fights. And they agreed to compartmentalize the border issue from the broader relationship. And in fact, trade between the two countries flourished. And the Prime Minister Modi and President Xi even began a series of informal summits after China in 2017 had infringed on disputed territory or disputed territory. That was really part of Bhutan in the Doklam area and occupied it for 73 days before backing down. And I think the Indians felt that the relationship, while not tremendous, was being managed in a positive way.

Amb. Juster: [00:34:06] And then we're shocked in about April of 2020, when Chinese forces were doing exercises in the Tibetan region and suddenly took a turn to the left and amassed 50,000 troops and heavy artillery on the northern border with India without declaring what their objective was. And we've speculated about that. But they have now stayed there for two years and dug in and building permanent infrastructure. This has been an enormous effort by India to respond and to counter that with its own troops. They've had shifting movements and for the first time in 45 years, there was actually violence in which 20 Indian troops were killed and at least four perhaps more Chinese were in June of 2020 in the Galwan Valley. This has completely shattered the trust that the Indians have for the Chinese. They've had numerous talks trying to resolve matters with very little progress, but without further confrontations, which is always a challenge when you have 50,000 people on each side poised against each other. But I think it's going to be a very long time, if ever, that you can put Humpty Dumpty back together again and and have a trusted relationship between India and China. And so what this has done is given further impetus to the US-India strategic partnership and to the development of the quadrilateral grouping of India, the United States, Japan and Australia. And so in a certain way, while those groupings have a rationale on their own, the role of China also stimulates their development even further.

Adm. Davidson: [00:35:47] One of the first things I did was call my counterpart in India and speak with him, and that was Admiral Lanba at the time and offered our support for anything that might be needed. One of the things that was very successful to helping advance the idea of Free and Open Indo-Pacific and the nation's Indo-Pacific strategy was to increase our transparency in several regards. One was with South China Sea nations so that they understood more clearly Chinese activities in the South China Sea. And then the second became the clash along the line of actual control. So with the authorities that I had and was given from the Department of Defense, we shared an incredible amount of information with India about activities that China was undertaking. We established a very firm and consistent what we call in the military a battle rhythm, which is an almost a daily routine of information that was moving back and forth from my intelligence organisation with Ken's team there to the attaché network and through the attache network in India and to their contacts there in the Indian military. And I think it was. Highly valued. That was certainly the sense I got in my conversations with the uniformed leadership in India and in many respects helped sue some of the early blows that were happening along the border. I think we found during my time at INDOPACOM and I would say as you look at the crisis between Russia and Ukraine right now, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine right now, information sharing and intelligence sharing is been an asymmetric, asymmetric advantage that the United States can offer our partners to be able to oppose authoritarian country move.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:37:42] I wanted to jump back to the Quad, which we've mentioned several times, and it's an important component of U.S. engagement in the region. Can maybe starting with you, can you explain what the Quad is and is not?

Amb. Juster: [00:37:57] The Quad first came about in response to the tsunami of, I believe, 2004, in which these four countries were providing humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. And it began to meet formally in 2007. As I indicated, it was initially a vision, I think, of of all the leaders, but the Chinese quickly objected, and by 2008, the Quad had sort of dissipated. The Chinese felt that it was some sort of gathering to contain China, and it was an objective of the last administration to resurrect the Quad. And we began working on that in 2017. And after we got countries to agree on the importance of the Indo-Pacific region, we were at the working level, the assistant secretary level and ambassadorial level, trying to get Quad meetings among folks from the four different countries and finally developed a ministerial level Quad meeting in 2019 in person on the margins of the UN General Assembly in New York, and then 2020 in October in person in Tokyo and the Quad, while it was originally designated as the Quad Security Dialogue and does concern itself with maritime domain awareness is sensitive not to be viewed by China or other countries in the region as a military grouping akin to something like a NATO of Asia. And instead it's tried to develop what it views as a positive agenda dealing on vaccine coordination, critical and emerging technology issues, climate and technology matters, cyber security, infrastructure, and other areas where it believes it can play a positive role in helping the global commons, so to speak, and building a strong architecture in the region which may be viewed as an alternative to some of what China is aiming to do, but is not presented in that way. And so it has been elevated by the Biden administration to this summit level with leaders. They've had a virtual meeting and an in-person meeting. They'll have another one this year. And it really is been very important in developing the broader principles that all of these countries want to see enacted and upheld in the Indo-Pacific.

Adm. Davidson: [00:40:24] One of the things that struck me immediately after assuming command INDOPACOM was the performance of the Indian Navy during the 2018 rim of the Pacific Exercise in and around Hawaiian waters. The ship that was involved just did a tremendous job and really made a strong impression on all the other nations that participate in RIMPAC. So for those who don't know, during the last decade, after the 2004 tsunami and for several years afterwards, India, Australia, Japan and the United States exercised at sea in an exercise called Malabar that had come apart. And while it had continued in fashion between the United States, India and Japan, it had excluded Australia for a number of years due to India's feeling that Australia was just a bit too close to China, Australia, Japan, myself, the leaders of those two general staffs in Australia and Japan engaged India over time and hopes to restore the Malabar exercise. And I think one of the key results of the Quad, while it may not be deep as a security relationship that has restored the Malabar exercise as a quadrilateral exercise between India, the United States, Japan and Australia. And I think that sends a very, very important message to all of our allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific, but certainly those in Southeast Asia and along the rim of the South China Sea, that this grouping of four democracies and their naval forces is sends. Birds are a powerful signal. The free and open nature of the seas and airways that we hope for in the Indo-Pacific.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:42:13] To wrap up, I wanted to ask one last question. Some see greater U.S. involvement in presence in the Indo-Pacific region as merely a response to the growing power and presence of China. As you correctly noted, Admiral, quote, "The strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific is not between two nations. However, it is a contest between liberty and authoritarianism, the absence of liberty." So my question is, beyond competition, what is the United States trying to build in the region and how important is this region to U.S. national security?

Adm. Davidson: [00:42:52] Well, Deborah, I'll take the last part of your question first. And I think the simple demography of the region speaks to what the US interest is right before the decade is out, two thirds of the world's population and two thirds of the global economy will be centered on Asia. The prosperity and security that the United States has enjoyed since the end of World War Two is is in large part due to its leadership in the International World Order. For me personally, and Ken might see this a bit differently. You know, the Chinese have made quite plain what their intent is in the decades ahead, and that is to supplant the US leadership role in the international world order and replace it with one with Chinese characteristics. And one only needs to look at what's happening in Russia and Ukraine to understand how a close and authoritarian nation will approach its neighbors and the international world order. It's a tragedy. We cannot afford to wait until the region is in ruins. We have to move in advance of that to preserve our leadership.

Amb. Juster: [00:44:06] I would agree with and amplify what Phil said. The Indo-Pacific region is really becoming the center of gravity of international affairs. As Phil indicated, it's got the world's largest economies, the world's largest populations, more than 50% of international trade goes through its waters. It's got enormous natural resources. And the United States has been in the Pacific for over 100 years, and our future is tied in large part to that region. And so it's very important in the principles we articulated for a free and open Indo-Pacific, for the architecture we're trying to build, to have a strong India as a partner and a strong US-India relationship. And so there is a lot at stake for us. And that's why, from my perspective, and I think Phil's it was so important for us to be trying to build with our partners the most constructive architecture and set of relationships that we could.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:45:07] Well, I want to thank you. Thank you, Ken. Thank you, Phil, for stressing the importance of U.S. leadership in this key area, as well as conveying the complexities of carrying out our U.S. national security strategy in India.

Adm. Davidson: [00:45:23] Great to see you, Ambassador Juster, as well.

Amb. Juster: [00:45:25] Thank you, Deborah, and great to see you as well.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:45:28] Our series is a production of the American Academy of Diplomacy with the generous support of the Una Chapman Cox Foundation. You can find our podcasts on all major podcast sites as well as on our website GeneralAmbassadoPodcast.org. Please follow us on Twitter and Facebook and we welcome all input and suggestions we can be reached directly at General.Ambassador.Podcast@gmail.com.