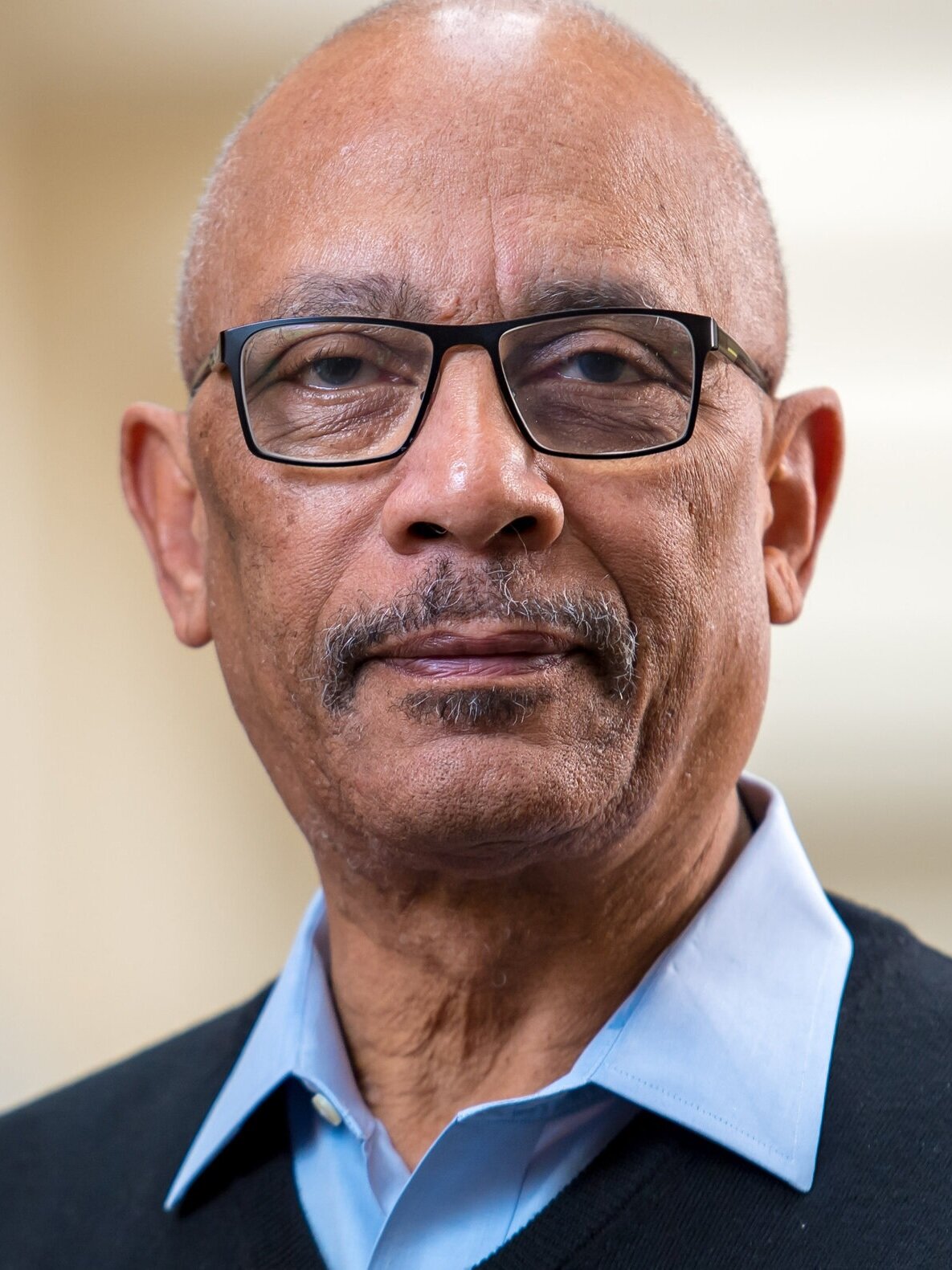

Episode 34. Fighting Terrorism is a Team Effort with General Francis Taylor and Ambassador Tina Kaidanow Part II

In this conversation, General Taylor and Ambassador Kaidanow talk about their joint work to prevent ISIS recruitment efforts in the US and abroad, to develop counter messaging to ISIS propaganda and to make sure key information was shared with local US communities. They discuss the surprising findings on who was vulnerable to recruitment….

Episode Transcript:

Amb. McCarthy: (00:00) Welcome to Part II of The General and the Ambassador with our guests General Frank Taylor and Ambassador Tina Kaidanow. By the end of 2015, 40% of the territory ISIL controlled in Iraq and Syria was liberated. Thanks to the efforts of our troops, today ISIL has lost its Caliphate. We've covered a portion of the military side of this fight in an earlier podcast with General MacFarland and Ambassador Jones. I wanted to talk to both of you about the non-military aspects of our government's efforts, and this includes efforts to get countries to pass laws to prosecute foreign fighters, to stop their travel, to cut off the funding and to tighten border security. We led an effort in the State Department to get the UN to pass a resolution which was called resolution 2178 which led many countries to pass or update the very laws I mentioned before. Tina, in your work at the State Department, can you tell us about what your team did to get this resolution passed and how many fighters were arrested or prosecuted as a result of tightening laws across many countries?

Amb. Kaidanow: (01:19) That particular resolution was designed to again, make sure that countries understood that they had obligations and they had an interest in undertaking a variety of efforts that, some involved prosecution, but others involved, as I said, border security, kinds of things that you know, obviously they're important to us and that some countries have the resources to undertake and some, it's harder for them. What we needed to do was encourage them both through the United Nations, and that's usually, when you pass a resolution, it's to that end, it's to ensure that they understand that they...

Amb. McCarthy: (01:50) Everybody agrees and starts taking action.

Amb. Kaidanow: (01:53) Exactly. Beyond that though, I would highlight that we also were generating a lot of interest in support for another organization called the Global Counter Terrorism Forum, which the United States helped found actually, but I had a number of other members as well and the idea behind it was a community of practice. So, in other words, a number of countries who wanted to assert the importance of fighting terrorism all over the world. How do you do that? You take your best practices and you share them with other countries. Not everybody does it exactly the same. Everybody's system is a little bit different. Everybody's effort is little bit varied. But that said, there is a way to do it and we can be helpful sometimes with funds, sometimes with methodologies like we send our experts over and say, okay, here's what you might be able to do. The one thing we found universally all over the world, you have to have your agencies talking to each other. So if your interior ministry is not talking to your foreign ministry, how are you going to ensure, for example, that the visa policy that you have in place is supportive of generating the kind of information you need? Who's coming into your country?

Amb. McCarthy: (03:01) Yeah, to track the tourists.

Amb. Kaidanow: (03:03) Right. Universally, you would find that there was difficulty or challenges in that set of relationships.

Amb. McCarthy: (03:08) Well, there's one law where the US seems to be quite unique and I want to ask you about this,, Frank. The material support statute whereby even traveled to join a foreign terrorist organization is a crime punishable in the United States by a prison sentence of 15 to 20 years. Very few countries have that. Has it ever been applied to returning US fighters?

Gen. Taylor: (03:31) I don't know that it has been applied to returning u s fighters, but it's been a very valuable tool for our FBI and I have to tell you, under Bob Mueller and subsequent directors, the FBI has transformed its way of doing business. They received laws like this law for enforcement that have allowed them to be proactive in engaging potential terrorist subjects well before they operate. I can't tell you how proud I am of how the FBI has transformed and how these laws help the FBI. At one point in time Director Comey indicated there were over a thousand people under investigation for counterterrorism in the US. These are people in the US under investigation by the FBI. That number continues at large, but the FBI has been very effective in taking these people off the battlefield before they're able to take action. We've had a couple, during this period we had, I think five terrorist attacks in our country--San Bernardino, Texas, the Pulse night club, the attacks in New York--so despite all of our efforts, there were still pockets of people who adhere to this philosophy and actually took action even with all the efforts that we were engaged in.

Amb. McCarthy: (04:50) Well, I wanted to get back to the information sharing. The U S has information sharing agreements with many countries to identify, track and deter the travel of suspected terrorists. Many of these are part of the packages that the State Department and DHS negotiate with countries in return for being included in what's called the visa waiver program, whereby their citizens can travel the United States without a visa. This applies to a number of countries, Germany, France, I remember negotiating with Greece when, when I was there. I wanted to ask you both, how would you assess the value of these information sharing agreements? Are they giving us what we need?

Amb. Kaidanow: (05:27) We play a role, a vital role. We're in charge, for example, of visa issuance and our consular folks are the ones that are dealing all over the world with these questions of who is eligible for a visa and who is not eligible for a visa and it's a very sensitive set of questions. You got to remember that at the end of the day, you know the purpose of letting people into the United States is because we are, a.) An open country because we have business interests all over the world. We have students that want to study in the US we have tourists come and spend money. All of these reasons mean that we have an interest in making sure that people can come to the US in a safe and understandable and reliable manner. On the other hand, we have to worry about who comes and might be a threat to us. What happened over the years is we created a set of criteria that would say to the countries, look, we'll continue to let you in, but you need to be able to share with us certain types of information on the individuals that are coming to our borders. Look, it's a sensitive question. Sensitive question for us here in the United States. How much information do you share about your citizens? What kind of information do you share? What ended up happening was again in coordination, for example with DHS, we would approach our allied countries overseas and we would say to them, okay look, if we're going to keep that door open, we need to know certain kinds of things. And some of the specifics had to do for example with who's traveling where under what circumstances. If you're an individual that for example is traveling one way from Istanbul to Baghdad and you drop off the map, that tells you something. If you are an individual who has spent an inordinate amount of time in certain places and then you come back into Europe and you sort of again drop off the map for a while, that's of interest.

Amb. McCarthy: (07:15) But decide you want to take a trip to New York?

Amb. Kaidanow: (07:18) Exactly. So these are the kinds of things that we told them, listen, we need more information from you on this. And by the way, we don't need it just on the basis of bilateral, country to country. We need it from, for example, the EU itself, the European Union needs to come up with this kind of information on a more systematic basis. That was quite difficult. It took us a while and we did this and coordinated between DHS and the US State Department.

Amb. McCarthy: (07:44) That's right because it's only recently that the EU has developed their own, what's called PNR passenger name recognition list.

Gen. Taylor: (07:50) Correct.

Amb. Kaidanow: (07:50) That's right.

Amb. McCarthy: (07:50) Each one had their own, And we encouraged them to do it all together, because before you could pass from France to Belgium to this and that. And nobody was tracking that.

Gen. Taylor: (07:59) There's nothing like a terrorist act to spur change. The individual who attacked Charlie Hebdo came back from Turkey into I believe a European country. That information was never passed back to the French to know that this guy had come in and they determined that because of that they could have interdicted him earlier than the attack. And I think the same was true with regard to Belgium.

Amb. McCarthy: (08:26) The airport attack?

Gen. Taylor: (08:26) The airport attack. The same was true with regard to the Bataclan. So Europe learned in two short years what 9/11 taught us on 9/12, that the failure to share information really created a danger to public safety and that began a process with the Europol, with the EU to exchange more and more information. Also, through Europol, in the aftermath of attacks, Europol was able in a coordinated fashion to support the French police or the Belgian police as they conducted their investigation because they had information sharing that made those investigations much more efficient.

Amb. McCarthy: (09:08) But Europol was the institution that pulls it all together?

Speaker 5: (09:11) The European Police organization of the EU, and they have become as effective as I've seen in Europe in terms of exchanging information among police agencies. But there's also a challenge sometimes unlike in our country where we share information between police, federal law enforcement, and intelligence agencies. That's not necessarily the case.

Amb. Kaidanow: (09:33) As I said, it's interagency coordination and in a lot of these countries it's extremely challenging. It's not that they don't acknowledge it, it's just that it's very hard to overcome.

Amb. McCarthy: (09:44) Well, I recall that in Greece, we worked as diplomats to encourage a better exchange of information amongst the Greek agencies. And they were literally meeting, trying to meet separately with the DHS representative at post the FBI rep at post, the intelligence rep at post, and once in a while the political officer. And we started a process of meeting all together with their key people so they knew that the kinds of information exchange we had, we wanted them to do because some of them were threats to us. Cause we've had attacks on our embassy in recent recent years.

Amb. Kaidanow: (10:19) Yeah.

Gen. Taylor: (10:19) Let me add, privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties are still at the forefront of how we think about information exchanges within our country and with our partners. And so while there's a great deal of concern around privacy, we try to exchange information but do so in a way that protects the privacy, not only of our own citizens, but the privacy of the citizens of countries that share information with us.

Amb. McCarthy: (10:46) Important point.

Gen. Taylor: (10:46) It's a very important point and it's getting much more difficult to do that. But it's at the essence of how we think about this, that we can analyze intelligence, we can analyze information and we can do so in a way that protects civil rights and civil liberties, but also allows us to make solid decisions about who we allow into the country and what their purpose may be in trying to come here.

Amb. McCarthy: (11:10) Well, I wanted to talk a little bit about Americans traveling overseas. I mean we've seen that there are attacks on soft targets. You know, I recall one in Nice that took place in 2016 where a man drove a huge truck through crowds gathered to celebrate the Bastille Day, killing 86 and injuring hundreds of others. Tina, let me ask you, how do we work across our system to quickly warn Americans who may be traveling?

Amb. Kaidanow: (11:37) Generally speaking, what I would say is the State Department is engaged with all of the intelligence agencies with all of our compatriots here in the US to ensure that whatever information comes through is properly and appropriately dispersed overseas in as timely a way as possible so that the best information we have, we can alert citizens to. It's sometimes, it's a judgment call. I mean, you know, there's all sorts of information that comes through. I mean Frank can speak to this, intelligence comes in all the time, particularly in you know, certain parts of the world where you know, Americans are not well liked or where there's a spike in violence or whatever happens. But once that determination is made, that indeed it may have some negative impact on American citizens, we have networks to get it out quickly. We have embassies that can then disperse that information and we encourage, of course, all Americans to go out and to register with our embassies so that we can reach out to them personally if we need to.

Amb. McCarthy: (12:34) We can find them in their hotel rooms or text them or whatever.

Amb. Kaidanow: (12:35) Absolutely. Yes. And we have done, believe me when I tell you, I think all of us have experienced this. When I was a Deputy Ambassador in our embassy in Kabul, we had numerous instances, you'd be shocked, private Americans were in trouble and you know, we would reach out and try and help them. As I said, we have a, I think, unparalleled system to try and ensure that our citizens are as well protected as possible, but at the end of the day, it's the judgment of each individual American, you know, should I be here or should I not be here? The answer is, listen to what it is that the embassy tells you.

Amb. McCarthy: (13:09) The security alerts the warnings...

Amb. Kaidanow: (13:11) Yes, make sure that you are alive to this because if you're not, you are missing a critical amount of information. Behind that goes an enormous amount of effort on the part of US agencies.

Gen. Taylor: (13:22) The State Department website is incredible, with information for American citizens. If you register, you'll get an alert. I had the honor of leading diplomatic security at a point in time and I know how hard our consular folks, security folks, our political folks work to ensure that if there is data of threats to Americans, that we will do everything possible to include public announcements in certain places to ensure people understand what that risk is and to have them take appropriate action to protect themselves.

Amb. McCarthy: (13:56) Both of you spent many decades in public service including many years at the intersection of security and diplomacy. What have you learned from working within Department of Defense, Department of State, Department of Homeland Security, about partnerships across government and their importance in protecting our country?

Amb. Kaidanow: (14:17) In a career of 25-26 years, the clear message is, if we don't work together to a single policy purpose, in this instance, it's counter terrorism, frankly, you can apply that same message to almost anything we do. If we don't have an integrated strategic approach, we will fail. I can tell you again, sitting in the Defense Department, same issues come up all the time. We need to talk to each other, but more than just talk to each other, we need to ensure that whatever we're doing, it's to a single purpose and that means, you've got to start early. Think about what is your purpose? What are you trying to achieve? How can the various agencies bring their own abilities and capabilities to that effort? How then do we all agree that we will pursue it and in what way? And in what timeframe and to what ends? To the extent we do that successfully, we find that we achieve our purpose and really that is the message of 25 years and if you don't do that, and that is also something we tell our foreign partners, if you don't do that, you will not succeed

Gen. Taylor: (15:20) And you will not protect your society.

Amb. Kaidanow: (15:23) That's correct.

Gen. Taylor: (15:23) I've thought a lot about this. I was in DoD in OSD [Office of the Secretary of Defense] Policy and Goldwater Nichols passed.

Amb. McCarthy: (15:30) I think you might have to explain what Goldwater Nichols is.

Gen. Taylor: (15:30) Goldwater Nichols was the law that forced the military to play together in the sandbox, after, I think it was 50 years, since the National Security Act in 1947, congress passed a law that says you must build joint structures. The joint staff will become much stronger than it was with the Army, Navy and Air Force operating separately. In my view, without Goldwater Nichols, we would never have been effective in Gulf War I. It changed the culture of how the military thought about working together and building structures and command structures and logistics structures and those sorts of things. I also remember sitting in the State Department on 9/11 at 9:30 on a global secure video teleconference with Dick Clark in the White House and other players around the counterterrorism security group and the feeling of how the hell did this happen and when you peel the onion back, you figured it happened because we weren't working together. We were working on purposes for which we thought were right. I'm not impugning the integrity of people who were trying to do their jobs. What they didn't understand, the purpose was to share and work together and that's what's happened in counterterrorism in the United States government since 9/11. It is the most coordinated aspect of how we do, I think, global policy. It works because now we've integrated not only the State Department, DHS, but our state, local, tribal, territorial, and foreign partners.

Amb. Kaidanow: (17:05) That's the point. Yeah.

Gen. Taylor: (17:05) The important thing there is that we all understand that this is all about protecting our citizens from this threat that knows no border, knows no nationality, and is hellbent on pushing an agenda that undermines the liberal order that we've created since World War II. And that to me is why it's so important. That's why information sharing is so important. Doing so in a way that protects privacy and civil liberties, but you cannot do good security without data. I tell the story of wider who was the sheriff of Tombstone, and he was the sheriff in town while tombstone was an island sitting in the middle of nowhere in Arizona and he could be the sheriff in town. There's no longer a Tombstone. We live in a global society. We live in a society where if we don't share information about threats and risks, we put the entire global system at risk. We've learned that lesson the hard way in the US, it's the partnership that Tina and I have had for the last 18 years and one that I think will continue to move towards the future.

Amb. McCarthy: (18:11) Well, Tina, Frank, I want to thank you for sharing the behind the scenes view of how you have worked, and our government works to protect the homeland and to push the threat out and thank you for that point in particular on the sharing of information, that Tombstones don't work. I really appreciate you taking the time. I know you're both busy still working on these issues in your current capacities and I hope as a result of your sharing that we get lots of questions from our listeners, so thank you.

Gen. Taylor: (18:38) Thank you for having us.

Amb. Kaidanow: (18:40) It's interesting to rethink some of the things that we went through, but it's clearly relevant still. Unfortunately, I mean I wish it were different, but this is an evolving and a dynamic threat. It's certainly the case that those who follow in our footsteps are going to have to think about the same questions, but in a different way.

Gen. Taylor: (18:56) I was asked, as Coordinator for Counterterrorism, I had to go to the North Atlantic Council to brief on the case against al Qaeda. I was in the FBI operations room, at FBI headquarters, and this was the 1st of October, and it's still an active investigation. And I remember to this day, Bob Mueller, the FBI had never allowed a State Department person to come into their operations room, in the middle of the investigations of 9/11. He says, "whatever you want, whatever you need, take it…"

Amb. McCarthy: (19:30) Good for him.

Gen. Taylor: (19:31) "To build your case." I took several slides from the FBI's wall as they were building the investigation, used those slides to go to the North Atlantic Council and brief the North Atlantic Council before they invoked Article V of the Washington Treaty. Cooperation works. It has proven since 9/11 to be effective and there are leaders like Bob and Tina and others who have made that happen. And I think that's so very important for the American people to understand.

Amb. McCarthy: (20:05) And a huge step to protect our country.

Gen. Taylor: (20:07) Indeed.

Amb. McCarthy: (20:08) Thank you. Thank you both.

Amb. Kaidanow: (20:10) Yeah.

Gen. Taylor: (20:10) Our pleasure.

Amb. McCarthy: (20:11) And that is it for this episode of The General and the Ambassador. My guests today were General Frank Taylor and Ambassador Tina Kaidanow. This program, The general and the Ambassador, is a project of the American Academy of Diplomacy and the Una Chapman Cox Foundation. You can find us on all podcast sites and we urge you to give us comments and great reviews. We would love to also hear from you on suggestions for future episodes. You can reach us at generalambassadorpodcast@gmail.com and our website is generalambassadorpodcast.com. I am Ambassador Deborah McCarthy and thank you so much for listening.